Mama Shakes' accent is all but gone now, although when she speaks to her brother, or Aunt Gladys, who still live in New Yawk, it creeps back out, and I am reminded of why I thought for years that the word spatula was spelled "spatuler," and why my classmates always giggled at my pronunciation of the word horrible.

At home I was Lissa; at my grandparents' house, I was Lisser. "Lisser'n I aw gunna wawk down to the cawnaw stoah." It was almost a different language, but I spoke it—and I knew it meant I was going down to the corner store with my granddad, where he'd buy a paper and give me some change to buy 5¢ candies kept in big glass jars on the countah.

It was the language of summertime. When school let out, including for my parents, who were teachers, we went to New York, driving across the country—Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania…—and by the time the Verrazano Bridge was in view, I was giddy with anticipation of hearing that language again. Lisser, New York called to me. Lisser. All the mystery of a magnificent city wrapped up in a voice that made my name thrillingly unfamiliar to my own ears. I never got used to it, because I never wanted to. I preferred to let that language remind me always of the chance for exploration and wonderment that a city which wasn't my own provided.

I loved (and love still) Central Park, and the Empire State Building, and the Statue of Liberty. I loved the subway, and the ferry, and the Queens-Midtown Tunnel on the Long Island Expressway. But everything I loved the most could be found on one block on 68th Street in Queens. Cellar doors on raised cement porches, fuzzy white caterpillars in the narrow, kid-sized crevices between row houses, my grandmother's desk whose drawers were filled with outdated secretarial tools that fascinated me, my grandfather's closet with its old-fashioned hangers and shoehorns, the dumbwaiter that ran to the cellar, the pocket door between the living room and kitchen, intricate metal heating grates, an ancient wallphone with a phone number written on it that contained letters, the best junk room in the world stuffed with a working electric organ, a massive collection of Mad magazines, and a box of funny hats. And my favorite thing in the world—the giant, steel kitchen sink, that doubled as my bath when I was a wee thing.

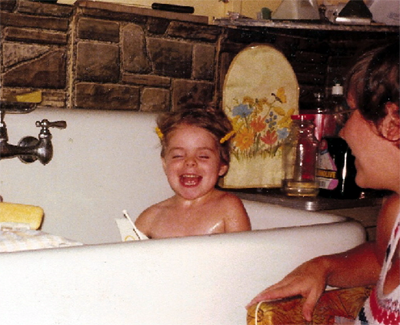

Lisser, my mom would say. It's bath time. The cold sink would be filled with warm, soapy water, while I waited patiently in my toddler chair with its vinyl seat and cool metal arms. And then I would be undressed and lifted into the sink, where I'd slide against its smooth sides, and my mom would have to reach in and pull me upright again as we both laughed. My grandmother would tell me about how she and my mom and my uncle were bathed in that sink, too; We'll look at the pictures later, Lisser. Later…when I was wrapped in my big green terrycloth towel, complete with a hood, that was perfect for snuggling after a bath—or wearing to play Robin Hood any old time.

Once I was too big to be bathed in the sink, it became a benchmark for how grown-up I was from one summer to the next. I'd stand before it and stretch in my arms, to see if I could touch its deep bottom. Maybe next year, Lisser. My fingertips reached its depths the same year my grandfather died.

The last time I stood at that sink, my nephew was carrying the tradition of kitchen sink baths into a fourth generation. Look at your Aunt Lisser, he was instructed, for a photo. He giggled and slid across its bottom.

After my grandmother died, the house was sold, and I'm sure that antiquated old sink is now long gone, a victim to modernization. But the language that falls from millions of tongues reminds me of it still. Lisser, I hear—and it conjures sunny afternoons on Myrtle Avenue, the Four-Ones cab company, corner shop candies, the Hudson, my New York and everyone else's. And a kitchen sink.

Shakesville is run as a safe space. First-time commenters: Please read Shakesville's Commenting Policy and Feminism 101 Section before commenting. We also do lots of in-thread moderation, so we ask that everyone read the entirety of any thread before commenting, to ensure compliance with any in-thread moderation. Thank you.

blog comments powered by Disqus